South Gate

Community History

Situated less than twelve miles from downtown Los Angeles and just under twenty miles from Los Angeles Harbor, South Gate is a young city, having laid its roots in the last century and grown to maturity in the past sixty years. During the eighteenth century, the area between the San Gabriel Mountains and the Pacific seacoast now occupied by South Gate was home to at least two villages of Gabrielino Indians whose ancestors had settled the area more than two thousand years before. Spanish explorers first ventured to California in the 1500s, but it wasn’t until the late 1770s that the Spanish made a permanent imprint on the Indian lands, building missions and striving to convert the native peoples to Catholicism and to teach them to live as Europeans. By the late nineteenth century, the traditional Gabrielino way of life was no longer evident.

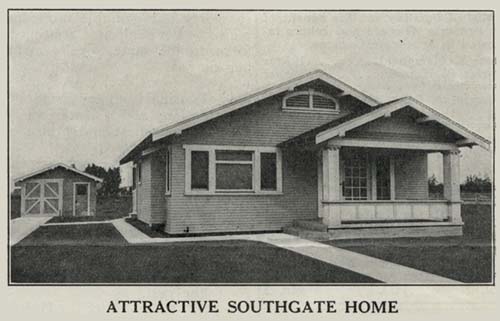

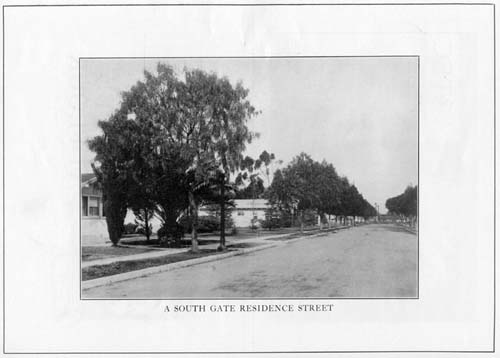

Spanish ranchers controlled the future South Gate lands during much of the nineteenth century, before their ranches gave way to dairies and vegetable and fruit farms. By 1917 developers saw in the cauliflower fields and apple orchards the potential for a shiny new residential community, selling tracts of land for houses and introducing an infrastructure that also beckoned Eastern companies looking to gain a foothold in the West to expand their markets. Though financial difficulties threatened to ruin the fledgling community in the 1930s, and an earthquake destroyed buildings and took lives in 1933, South Gate managed to pull through. War industries buoyed the town in the early 1940s, with industrial and population growth combining to spur the city’s continued success throughout the second half of the twentieth century.

Frequently Asked Questions

Leland Weaver, the owner of an insurance company and later a travel service, devoted much of his life to civic service and the betterment of South Gate. Born in Gardena in 1900, Weaver lived in South Gate for 52 years. During that time, he served for 24 years on the city council and as mayor from 1950-52, 1958-59, and 1962-63. But his contributions to South Gate went beyond holding public office. He helped establish a city swimming pool, a municipal auditorium, a girls’ clubhouse, tennis courts, and an art gallery. His commitment to the youth of his community also led him to active involvement with the Boy Scouts. Willing to give freely of his time, he served on cultural arts, beautification, and memorial fountain committees, as a member of the board of directors of the Salvation Army, and on the Metropolitan Recreation and Youth Services Council. He was also the first chairman of South Gate’s parks and recreation commission. A member of a multitude of other civic organizations as well, Weaver received numerous honors and awards from his community. He died in 1972.

In 1810, when the Spanish were gaining a sturdy foothold in Southern California, the King of Spain awarded Don Antonio Maria Lugo, the son of a prominent settler, a “vast acreage” (about 29,500 acres of land) which became known as Rancho San Antonio. A powerful rancher with a “magnificent hacienda,” Lugo not only owned many horses and cattle, but helped to govern the area. After 1850, his land was divided among eight sons and daughters, with portions eventually falling into other hands, including those of the Tweedy family which was to lend its name to a prominent South Gate street. In the late nineteenth century, dairy farms began to dot the countryside, with vegetable farms and orchards springing up alongside. Michael Cudahy, a meatpacker from Chicago, purchased several thousand acres in 1893 but died before he could introduce the pedigreed cattle and thoroughbred horses he intended to breed there. Following his death, the Cudahy Ranch Company was born.

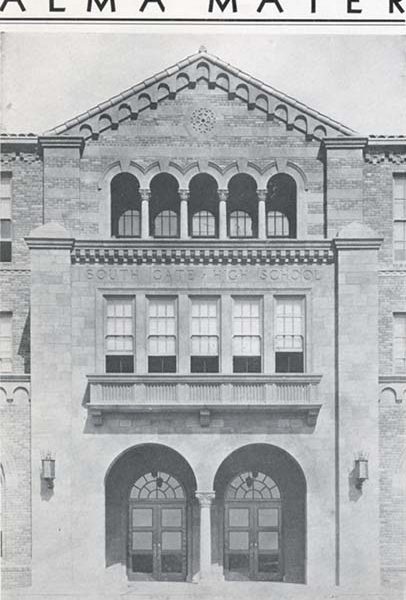

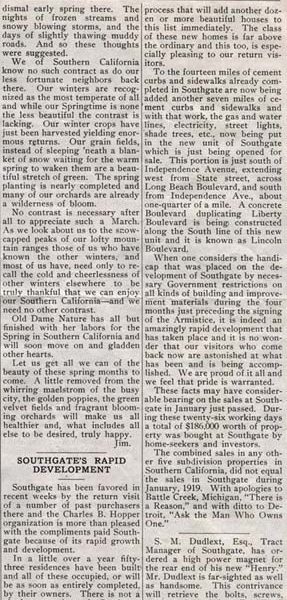

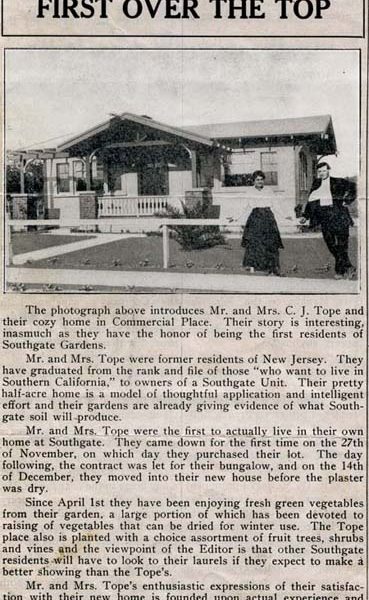

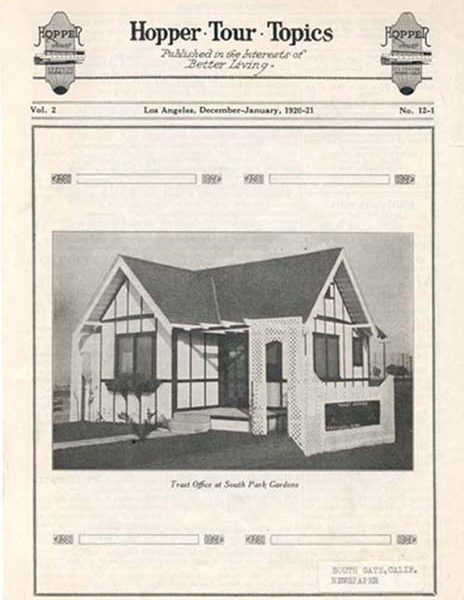

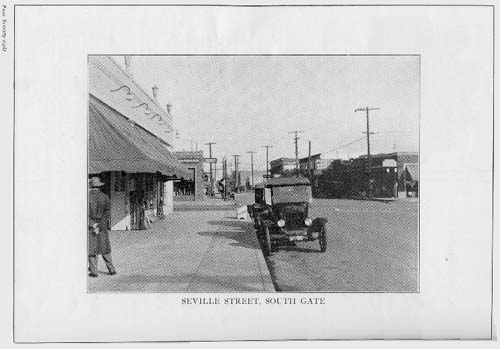

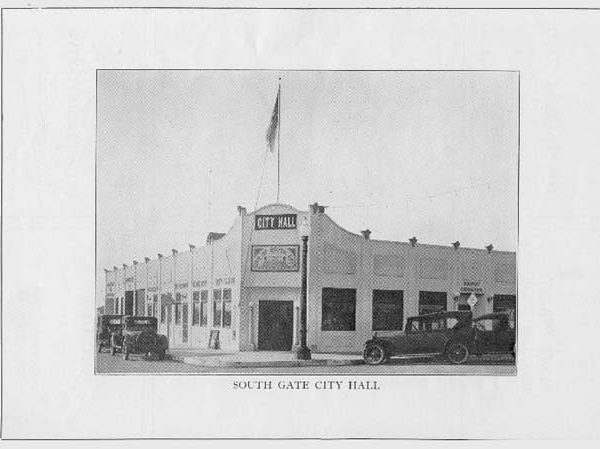

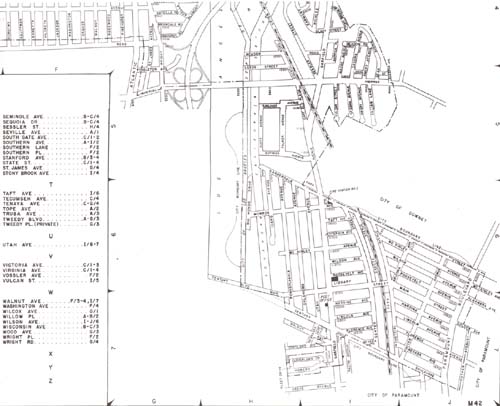

By 1917, the Cudahy Ranch Company had evolved into the Southern Extension Company and was advertising plots of lands for sale in a new community it was calling South Gate Gardens. Paved streets, water mains, and gas lines followed the construction of new homes, a business district was established nearby, and in 1923 community leaders convinced the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to incorporate South Gate as a city‹population: 500. During the Great Depression, the city experienced severe financial difficulties brought on in part by unwise spending decisions. In 1933, moreover, an earthquake measuring 6.3 on the Richter Scale damaged schools, businesses, and homes in South Gate and killed five people.

Despite these hardships, the city persevered, working its way out of financial trouble and rebuilding. An industrial base begun in the early 1920s grew and flourished during the 1940s in response to the demands of World War II. The influx of war workers and returning veterans sparked a postwar housing boom. In the years that followed, new inhabitants of diverse backgrounds arrived, working with the community’s changing industries to continue to shape the city’s economy.

Like South Gate as a whole, the Hollydale area began as a planned community, with a development company laying streets and sidewalk and constructing a handful of homes in the early 1920s. Factories quickly sprang up near the railroad tracks traversing the area, and a few shops and a post office soon made up a serviceable downtown. The onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s ended development for nearly a decade, leaving the scattered residents already installed in their homes as the town’s only inhabitants.

Under the federally-mandated Works Progress Administration, empty land between houses was rapidly covered with green cornstalks and leafy tomato and potato plants. During these years, the harsh economic conditions prevented some landowners from paying taxes on their property and other buyers soon stepped in, sometimes purchasing plots simply by paying back taxes. A building boom ensued and when World War II hit, new neighbors had joined the Hollydale community. The global conflict had an immediate impact on Hollydale’s citizens as the town’s factories got busy manufacturing materials for the war effort. Hollydale even had an anti-aircraft gun stationed near the railroad tracks behind a knitting mill that had begun producing aircraft parts.

In the years that followed, the community continued to mature and grow. Forty years after World War II ended, Hollydale was home to approximately 5,000 people. Having been annexed by South Gate early in its history, Hollydale has not always been completely satisfied with its status and has not lost sight of its unique identity, with some residents agitating for independence as recently as the mid 1980s. Nevertheless, at the dawn of the twenty-first century Hollydale remains an important part of South Gate.

Native Americans who lived in the Los Angeles area spoke a language distinct from their neighbors to the North and South of them. They have come to be known as Gabrielinos, because many of those who survived European diseases and the disruption of their normal trade patterns and culture went to the Mission San Gabriel, some voluntarily, others only when confronted by force. The Gabrielino lived in domed, circular structures with thatched exteriors. Both men and women wore their hair long and used a vegetable charcoal dye and thorns of flint slivers to tattoo their bodies. They required very few clothes, though women usually donned deerskin or bark aprons, and all might wear animal skin capes in cold or wet weather. Like most California Indians, the Gabrielino of the South Gate area ate roots and berries, rabbits, antelope, squirrels, crows, and other birds.

The first European to visit the future home of South Gate discovered many Indian villages between the Pacific Ocean and the San Gabriel mountains. Two villages, probably known as Tibahag-Na and Ahau, are thought to have been located within the boundaries of the present community. Passing through during the mid 1700s as part of Spaniard Gaspar de Portola’s famous expedition from San Diego to Monterey, Padre Juan Crespi observed that the Indians in the area were very friendly. Nevertheless, during the late 1700s and early 1800s, after dominating the Los Angeles basin area for hundreds of years, those Gabrielino who did not flee were gradually moved to Spanish missions. Many became laborers for local landowners. Most eventually adopted a new, more European lifestyle. By the twentieth century, few traces of Gabrielino culture remained.

In the 1800s, cattle ranchers occupied the land which was to become South Gate. In the latter part of the century, sheep grazing, dairies, and farming became common. An 1880 study reported that the key crops grown in the area included alfalfa, barley, beets, corn, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and pumpkins. This agricultural focus would continue into the early twentieth century. When in 1917 developers first sold tracts of land in the new South Gate Gardens, their advertisement talked of the many apple orchards in the vicinity, and prospective landowners who ventured out to view available tracts found broad expanses of cauliflower fields. Eventually these farms conceded nearly all of their territory to the new cities of Los Angeles County. [SOURCES: “South Gate 1776-1976;” “South Gate Police Annual 1927”]

What was his connection to South Gate? Although Glenn Seaborg spent his earliest years in Michigan, in 1922, when he was ten, his family moved to Home Gardens‹a community later annexed to South Gate‹where he completed grammar school. Seaborg went on to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry at the University of California at Berkeley and immediately thereafter joined the university’s faculty. Just three years later, in 1940, Seaborg discovered a new radioactive element, plutonium. His work led the U.S. government to call upon him for assistance during World War II. As part of the Manhattan Project, he developed a process that enabled the U.S. to produce a quantity of plutonium sufficient for an atomic bomb which was later used to bomb the Japanese city of Nagasaki. In 1951, he earned a Nobel Prize for his discovery of plutonium. In his work at Berkeley, Seaborg participated in the discovery of a total of 10 elements and more than 100 isotopes of existing elements. A man with a busy and varied career, Seaborg also served as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, chancellor of UC-Berkeley, a founding father of the Pacific 10 athletic conference, and an activist in support of a number of causes. In 1994, the scientific community named a new element seaborgium in his honor. He died in 1999 at the age of 86.

Glenn Seaborg Dies After a Life Integral to History of 20th Century

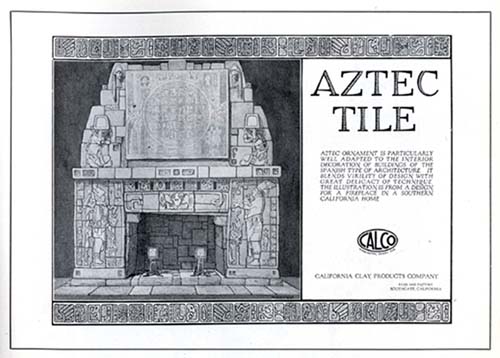

Nearly from the city’s creation, industry was part of South Gate, with early real estate literature emphasizing the industrial advantages of the area. The city’s founders recognized that for a city to grow, it needed jobs for present and future citizens, and industry represented jobs. Just a few years after developers sold the first plot of land, South Gate had welcomed a number of small industries. A.R. Maas Chemical Company, a firm later bought by Stauffer Chemical Company, opened its doors in 1922. Bell Foundry started operations in 1923. Firestone Tire and Rubber Company followed, digging up a bean field to build a new factory that it hoped would facilitate distribution of its products on the West Coast. Royal Dairy Farms arrived soon after. Attracted by inexpensive land as well as easy access to light and power, water supplies and sewers, and major highways, railways, and waterways, Star Roofing Company (later U.S. Gypsum), General Motors, and the American Concrete and Steel Pipe Company were among the firms that arrived in the vicinity in the 1930s.

By 1940, South Gate boasted more than 35 factories manufacturing chemicals, furniture, roofing, machinery, and other products. This industrial saturation meant South Gate was a hive of activity during World War II, filled to the brim with war workers keeping machinery humming from early in the morning until late at night, if not twenty-four hours a day. When the war ended, many workers who had moved to South Gate to keep the factories running decided to remain. In 1945, South Gate organized a Chamber of Congress which began promoting the community, luring still more industrial operations to the area. In 1976, over 400 industries were operating in South Gate. While General Motors and Firestone eventually left, other firms took their places. The remaining industries, moreover, continued to play an integral part in the life of the community.