Strong Arms

I was born in Los Angeles, California. My mother was not.

Fifteen hundred miles from Los Angeles, as a pajaro flies, about halfway between Quiroga and Zacapu along Federal Highway 15 in the Mexican state of Michoacán, is the small village of Caratacua. With a hundred residents, it is no more than a brief rest stop on any traveler’s journey.

There is not much to catch the eye of a passerby, except for, perhaps, the fields of wild, pink mirasol flowers. But to me it is a crib of history, the family ranch, on a gently sloping hill beneath an old Jacaranda tree where my grandmother and my mother were born.

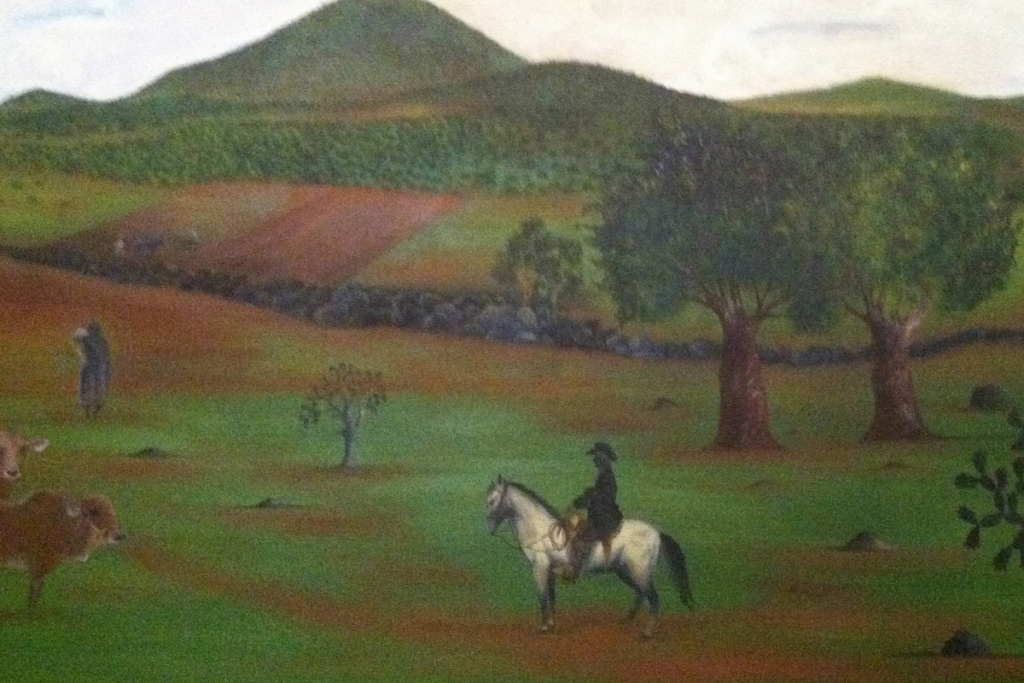

My grandfather, Papá Chuché, and my grandmother, Mamá Lola, started a family on that ranch, known as “Xaratanga.” It was named for the Moon Goddess of the ancient Purhépecha people, who inhabit the region and sprung from her seeds. It is where my grandmother resides today at more than 100 years of age.

Papá Chuché, a distinguished-looking man, lived into his nineties. He had a wandering spirit, and made a lifetime of treks into the U.S. He first entered the country under the Bracero program, picking Washington watermelons and Calexico cotton, but eventually he traveled all over the border states.

With each trip north, he left behind a bigger family in Mexico. They didn’t want him to go. But they needed money and when the dollar beckoned, he went, like so many others. Each time he came home our grandmother would exclaim with joy – her pajaro, like a hardy bird on a north-and-south flyaway, had returned to her again.

My mother is the oldest of nine surviving children of Mamá Lola. A sister, Delia, died at one year old from complications of dehydration, but really from the lack of medical care then in rural Mexico.

From Xaratanga my mother watched her father go. She felt deeply attached to Papá Chuché, loved him dearly, and suffered from his departures, if only to herself. Why he left them for months at a time, she did not understand. Yet she clung to the vision of seeing him return once more from each trip, bearing gifts. When he came, she would rush into his strong arms.

As a child in Xaratanga, feminine clothing caught her eye: garbs of cinnabar, flowery frills, and tender textures. But she would never ask for them. How could she? On the ranch, life was hard; fashion was an unspoken aspiration. Still, Papá Chuché managed to come home from his trips with at least one new dress, a shiny piece of jewelry, or a roll of fabric to set free her imagination.

Each gift, like the red dress he brought her once, was special and made her happy. She reveled in the intricacies and colors of the cloth he carried back for his little girl. That ritual came to be consolation for her father’s recurring abandonments, and part of the fascination with the country that lured him from her.

She still spontaneously mutters, “Cómo recuerdo un vestido rojo de pana que me trajo mi papá!”

There was one gift he brought at times, however, that was never for her: big, odd-looking suitcases. Those went to her mother and with her they remained at the ranch to this day, along with a special sewing machine.

For four years, when she was older, my mother went to the neighboring town of Pátzcuaro to study dressmaking, and learned complex embroideries, “canastillas de bebé” for newborns, and myriad other ways to turn fabric to fashion.

Yet as her father, a veritable charro, mounted his horse and rode away to El Norte again and again, his absence dug a hole deeper than any well outside the village.

Some of his children cried. Some drank. As the eldest child, and a girl, my mother could do neither. Instead, she sang. My mother loved music. When her feelings were strong, her singing was stronger. To this day, the words of the singer Cuco Sánchez fill her home: “Anoche estuve llorando, horas enteras, pensando en ti… Después me quedé dormido y en ese sueño logré tenerte en mis brazos… ”

Other times her grief found comfort in her mother’s cooking. Capirotada de pan Comanjo, torejas con dulce, and sopa de habas frescas.

When Papá Chuché was home, the feasting was special. He was a hunter with a .22-caliber rifle who’d set off into the hills surrounding the ranch in search of game, her younger brothers tagging along. Hunting was not something a girl did – but she would wait for him at the edge of the ranch atop a stone fence. Then he’d faithfully reappear with the boys, an armadillo, taquache, or zorillo swinging in hand.

The glittering hills surrounding the ranch on a clear moonlit night beneath a blanket of stars made Xaratanga appear a magical place. Sometimes at night when her father was away in the North my mother’s grandmother, mother of Papá Chuché, would call her to the patio of the ranch house at bedtime. They would hook their arms together. The old lady would face El Norte, raise a hand and make the sign of the cross, blessing her son – “que Dios lo bendiga …”

During one such magical night as a little girl, my mother heard the sound of the ears of corn brushing against each other, and saw the tassels of the corn swaying in the wind, as if waving her onward. She promised that night to God and herself, she tells me now, that one day she would go.

In time, my mother came to loathe her life on the ranch. “No hay vida,” she would say to herself.

There was plenty of work, but none that paid. Her chores were unending. Her arms ached. Even the name of the village – Caratacua – she despised. It was the word for a weed common to the area. The branches of the caratacua were bound and made into brooms for girls to use in their sweeping. She tired of the endless sweeping the rocks from around the ranch house.

Every Saturday, by 6 a.m., she’d pack a burro heavily with dirty laundry and trek several miles downhill to the local springs. On her hands and knees, she would find a suitable rock and scrub laundry against it for the rest of the day. She’d wash each piece and lay it out. By sunset, she’d fold each piece, now dry, and bundle it back onto the burro. The only thing that made her forget her aching arms were her legs as she made her way back up the hill.

My mother would help prepare and carry meals out to her brothers who were harvesting corn in the fields. Like her mother, she’d sling a big basket, a “chunde,” filled with tortillas, beans, nopales, and other favorites, onto her shoulder to take to the hungry boys who from age six learned to work the fields from dawn to sunset. After the meal, the chunde would be filled with the fresh corn. To this day, her love of Mexican corn on the cob, brushed with melted butter and sprinkled with chili powder, cotija cheese, and lime juice, remains.

Still the village could just as easily have been named “Piedras,” she thought. There were so many rocks. The fields were covered with rocks, on the surface and below ground. Some spots were so fertile that anything would grow. But in many places the rocks beneath would impede any root trying to take hold – the legacy of volcanic activity across the eons.

When my mother was a teenager, Petronila and Genaro, longtime neighbors from an adjacent ranch, left in search of work, never to return. So did others. The lifeblood of Xaratanga slowly bled out.

So, the stories her father told of life in the U.S. mesmerized her. She imagined riches for the taking. How wonderful must be this place, California, to prompt a man to leave his family, she thought. There, she was sure, she could buy herself a home in a big city, and a little green car to drive around in forever.

She let herself believe it was so. It was easy to do. Papá Chuché was such a positive man in a trying world, chronically genial.

“Solo los pendejos andan triste,” he would say. Only idiots go around sad.

She longed to find out for herself. She was the eldest child, a woman, and expected to work to help her mother to support her younger siblings. But she needed more than just being needed.

Then one day she remembered her vow and quietly left it all. She walked away in the early morning, aided in her escape only by a younger brother, who promised his silence out of deference to the sister who raised him.

My mother had kept in touch occasionally with a cousin, Victoria, who lived in California and who had once invited her to visit. She pawned her beloved Singer sewing machine and boarded a bus bound for Barstow, buoyed by the hope that her cousin would welcome her. She didn’t tell her cousin she was coming. She’d be there faster than any letter.

When she arrived, however, she learned Victoria had died a few months before of leukemia. My mother pondered her dilemma that first hot night in Barstow. She knew she could not stay now. There was no work in Barstow for her. Her cousin’s family let her stay for the night. But what then? Return to Xaratanga empty handed?

That night, as she fell asleep, she remembered her father telling her stories of a great garment industry in Los Angeles.

With her strong arms, she hugged herself, cuddled into her cousin’s sofa, and imagined the fashion that a dressmaker could create with all the cotton her father had picked.

June 4, 2015