Tia

Joanie was the firstborn of nine – the love child of a young girl and an adulterous older man. Her mother, Rosana, had two more children with this man but finally left him when she accepted he would never leave his wife. As the years went on, more siblings were born with various fathers.

Rosana was one of the few things they shared. She was young; she drank and knew men. She wore tight black pants, tight low-cut blouses, black hair teased high on her head, and a tattoo on her bosom. Once Rosana’s mother got fed up with the borderline negligent situation in which her grandchildren lived. She rescued them from Rosana’s house and resettled them at her own place. Eventually, though, the children drifted back to their mother one by one.

Joanie was their shepherd. She strived to be a good example and take responsibility for her flock of little brothers and sisters. She gave them the love and attention that Rosana did not.

Joanie strived to get her siblings to church; she would call different churches each week and make arrangements for her siblings to be picked up by van. She made sure each of her brothers and sisters had a present on their birthdays. She would scrimp and save her babysitting money to buy them a trinket, or she would make them a gift. On the summer days when Rosana would drop off the kids at the park (sometimes with lunch, sometimes without) it was Joanie who kept a watchful eye on her brothers on the grass and her baby sisters in the playground.

Mother and daughter were close at times, but Rosana would also shove, yell, and throw things at Joanie. One stepfather who passed through was just mean. If he didn’t like the food he was served he would throw his plate at the wall.

Outside of her home Joanie was a normal teenager. She dressed in the “chola” style that was popular in the 1970s, but she had good grades, loved music, and she played in her junior high school marching band. She befriended nerds and cholos alike.

Eileen was her best friend. They went to the 8th grade dance together and danced to funk music during lunch. Joanie came to Eileen the first time she had feelings for a boy. Joanie was so scared, not sure if she could be involved with someone – not sure if she should say something. Eileen gave her the courage she needed.

“Joanie – I love you, and you deserve to be in love.”

One October day, Joanie’s date, Jim, came over. Jim asked Rosana if he could take Joanie to a family party. Joanie felt Jim’s family didn’t like her and that she would never be good enough for him. Rosana initially said no. But Jim pleaded; he promised he would have Joanie home early. Rosana relented. As Joanie walked out the door, she looked back. It struck Rosana right then that that might be the last time she saw her daughter alive.

At the party, Joanie and Jim got into an argument. Joanie left on foot, alone, in a dark and lonely part of town. Presumably, Jim let her go. After blocks into her journey she made it to a pay phone. She called and called. Rosana wasn’t home. The children who answered had no way of helping her. Joanie called Eileen. Eileen wasn’t home, either.

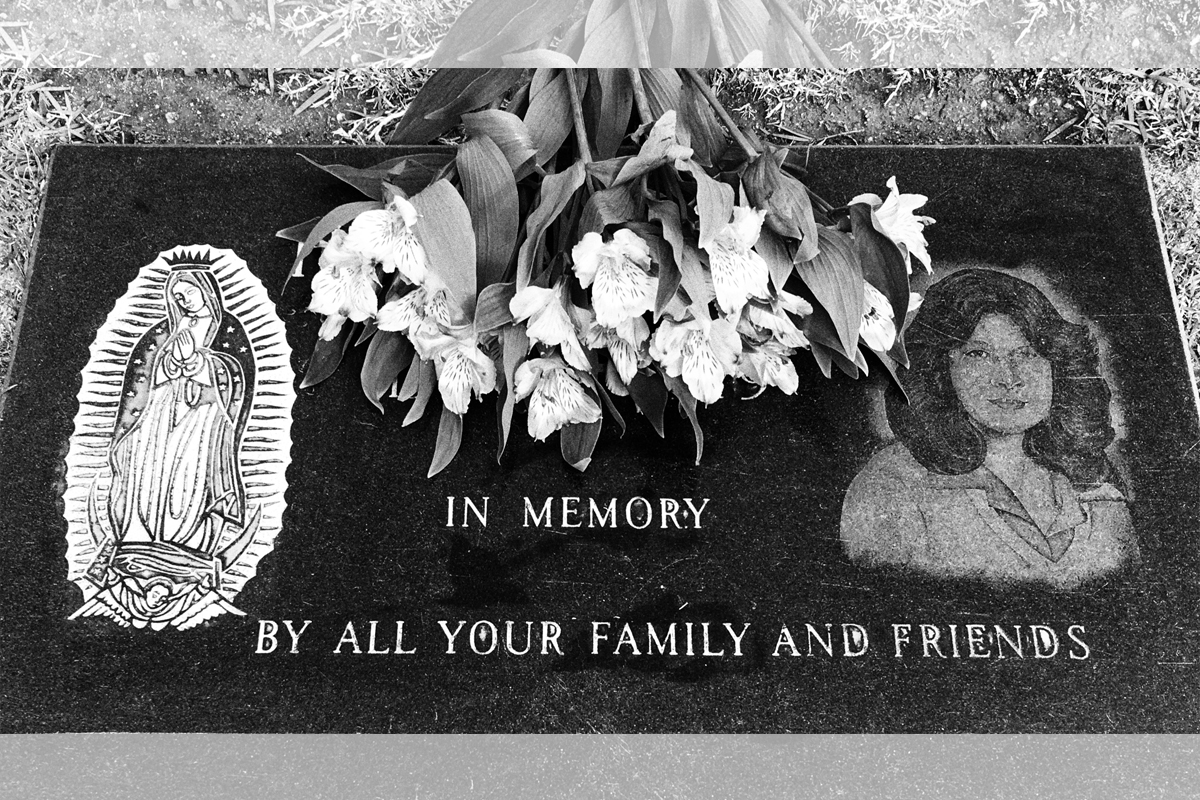

Joanie’s body was found not far from her home, in a deserted area, with unspeakable things done to it. To this day no one has been arrested for Joanie’s murder.

The school held a moment of silence in Joanie’s honor. Some people claimed to be closer to Joanie than they actually were in hopes of seeking attention. Money was raised in Joanie’s memory. Even though he had little to do with her in life, Joanie’s father was contacted and it was he who decided on her final resting place and paid most of the expenses. Hundreds attended Joanie’s funeral.

Following Joanie’s death the family fell further from grace. The older boys had matured into a posse of gang members who used drugs and alcohol. A couple of the boys did their best in athletics and high school life. The two girls mostly kept to themselves.

Wild parties became the norm at their house; Joanie’s now teenage brothers drank too much and passed out. Rosana turned a blind eye, even when her son was asleep on a cold night without a blanket on the dewy lawn. To the neighbors it likely looked like poor parenting from a woman with too many kids to parent. In hindsight Rosana was probably lost in her own grief, trying to forget that she was not there when her daughter needed a ride home.

Joanie was my aunt. She died five years before I was born. My father asked Rosana for permission to name me after her – but Rosana couldn’t give it.

My mom joined the family when she was 16, too young to understand what she was getting into. In the early years we were close to Dad’s family. They helped us secure a spot in the same apartment complex they lived in; so family was just down the driveway. Aunts and cousins running back and forth between the houses was the norm. Mom used to tag along on shopping trips. My cousin and I played Ding Dong Ditch between the houses.

Yet before I reached 10 Mom knew she wanted out. Arguments erupted behind locked screen doors. My cousin didn’t want to help me carry books home from school because he was afraid he would get in trouble for doing it. There were tears and restraining orders against the kin that lived one house behind us. Dad was caught in the middle; a natural pacifist between two families that meant the world to him but could no longer live in peace.

When I was young I used to think that if Joanie had lived she could have kept the kids from drugs and alcohol, and led them away from all that. I would then have had a family on my dad’s side with aunts, uncles, cousins, and a grandma. She would have been my favorite aunt and would have understood me.

When I was a kid Joanie’s picture was on the living room wall. Visitors would ask when I had my picture taken, my parents would reply, “That’s not Sarah; that’s her Aunt Joanie.” Our resemblance was uncanny. When I was a child I would stare at Aunt Joanie’s portrait and use it as a window to accept myself. Knowing that I looked like the beautiful young lady in the picture steadied my self esteem.

Now that I’m older my features have changed in ways that hers never had the opportunity to. I miss hearing people exclaim, “Wow! I thought that was you! You guys look alike!” Our physical likeness has faded, but our kinship has grown.

I wonder if she would have been “Auntie” or “Tia,” or simply “Joanie.” She’s the older sister I wish had been there for my dad in his times of hopelessness. She’s the aunt I longed for when I felt so lonely amid the family chaos. She’s the kind older sister, who would do anything for her charges, that I strive to be like.

The family felt the wound of Joanie’s death for years. Because of this, I only recently found out where she was laid to rest. Almost weekly now I sit here with Joanie. I unfold my picnic blanket. I have my coffee. I eat my croissant. I tell her why I picked the flowers that I did, and what kind I might get next time. I think about what people have told me, about how she was. My connection to her feels as real as the grass I stroke beneath me and the breeze that kisses my nose.

January 11, 2016