Bending Branches

The wooden mess hall was filled with the warm smells of coffee, eggs and bacon. Over 300 workers from Mexico filled up on breakfast for the long day of harvest. The bell rang. They grabbed their sack lunches and jumped onto trucks that took them to the almond and plum fields.

Miguel had arrived at the labor camp in May, a month prior to his 18th birthday. A year before, news filled his village in Mexico about the agreement between Franklin D. Roosevelt and Mexican President Miguel Avila Camacho to bring Mexican workers north to rescue U.S. crops from spoiling during World War II.

With a handshake, Miguel pre-sold thirteen bushels of wheat for thirteen silver coins from his father’s farm and ran away from home. He got to Mexico City and camped out at the Estadio Azteca coliseum with thousands of men waiting to be selected to become Braceros, farm workers sent north to help save the crops and feed millions of U.S. soldiers. Weeks later, he was put on a train with hundreds of men headed north. They arrived in El Paso, Texas switched to U.S. trains escorted by the Air Force and continued to California.

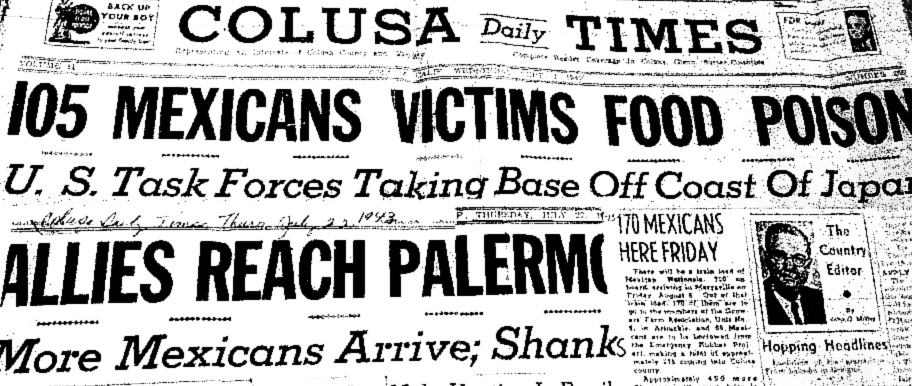

He arrived in the town of Colusa in 1943. That year Mexico sent 64,000 men to help the United States. As newspapers in New York and Los Angeles ran headlines of the war — “Allies Reach Palermo” and “Germans Fight to Stave Off Doom” – out in Colusa the local papers reported daily on the Braceros’ progress:

“170 Mexicans Here by Friday” and “Mexican Labor Pours into Colusa, 650 in Sight.”

Colusa County built housing at the fairgrounds to welcome the men. With retired Army Captain Herbert in charge of the Growers Association Labor Camp, the men learned army protocol. Years later, Miguel would still make his bed military style and talk about how he and the other Braceros served as soldiers in the war effort.

The day Miguel received his first paycheck he walked out to the road. Within fifty feet of the camp’s gates a man stopped to pick him up. No Bracero, he learned, ever spent much time walking on the main road without someone offering a lift. Miguel and the driver greeted each other. Neither spoke the other’s language, so they sat, smiled and nodded. The man dropped him off in town.

On Market Street, the local newspaper snapped photos of the Braceros. “These young and swarthy Mexican huskies have just been fitted at the J.C. Penney company store, healthy enthusiastic and ready to go,” read one caption.

Miguel walked into a store and with the help of gestures to a sales person he bought underwear, socks, shoes, a shirt, a hat and his first pair of Levis. He put the clothes on in the store. He smiled at his new look, gave the cashier five dollars and got change in return. He threw out his worn clothes and walked on to Market Street.

Miguel was full of hope and proud of his decision to leave home. But the work on the fields was rough.

In August, three months after their arrival, his group was sent to a field covered with trees bent under the weight of almonds begging to be picked. He and the others put their lunch sacks aside and placed large tarps under the trees. Miguel picked up a rubber sledgehammer and hit the tree trunk. Almonds stormed down like hail. Workers scooped them off the tarp and packed them into metal bins.

They moved row by row as the sun beat down.

The heat reached over 100 degrees when the whistle blew at noon. The men grabbed their lunch sacks and sought shade under the trees. Miguel pulled out an apple and admired it before taking a bite. He had never seen such a huge apple. Next he began to eat the sandwiches. They tasted odd, so he did not finish them. The break ended and the men returned to harvesting the burdened trees.

Two hours passed. As he worked the sun pierced his eyes and he began to feel light headed. Now cold sweat ran down his face. His stomach cramped and the ground beneath his feet turned rubbery. He looked out to the field. All over men held their stomachs. Others bent over vomiting and some sprawled on the ground.

The foreman ran back and forth yelling orders. Miguel was pushed into a truck full of sick, disoriented men. As they moved through the roads he fought the urge to vomit. Every bump and turn felt like a kick. He heard the blaring sirens and the roar of passing trucks. He tried desperately not to lose control.

That day 105 Braceros took violently ill in the fields and packed the two hospitals in Colusa County.

Men were treated on the floor of every corridor, x-ray room, waiting room, and ward of the rural hospitals. Only two doctors were on duty. The nurses, Red Cross and town volunteers joined to help the men. A handful of locals spoke Spanish and ran from patient to patient interpreting for the medical staff.

The sound of his thumping heart filled Miguel’s ears. He was able to walk and moved through this chaos. He did not understand. He left home, went hungry and homeless to get to the United States. When he registered in Mexico City he was told that he would be serving his patriotic duty saving crops to fight the enemies of the Americas. Now he and his compatriots were poisoned. He found an open door and ran.

Years later, he would not remember how he traveled miles to a nearby camp. But he found a shower and opened the cold valve. The water felt like a storm. He stood there washing the toxins from his body in a panic. The room grew dark as the sun went down. Still, he stayed in the shower, and went in and out of delirium for hours.

Then a voice.

“Son, are you okay?”

A grower took him back to the main labor camp. When they arrived Miguel saw men congregating in front of the mess hall as police and county officials investigated. Those in charge only spoke English.

The Braceros understood very little. They talked among themselves trying to make sense of the situation. Some talked about deserting and going back to Mexico. Miguel learned one of the men from his home state had died. He heard of others near death.

Officers escorted Asian mess hall workers to waiting police cars. Rumors spread that the workers were Japanese and had intentionally poised the Mexicans to sabotage the War Food Program. Over a third of the men were in the hospital. Those at the camp refused to eat and did not sleep much that evening.

In the newspaper the next day, the headline “U.S. Forces Raid Japan” shared space with “105 Mexicans Victims Food Poisoned.”

This was Colusa’s first large emergency. State and federal representatives investigated the cause of the poisoning. The official statement was that the outbreak was due to excessive heat combined with a lack of refrigeration for the hundreds of lunches served.

The Mexican government sent a representative to address the fears of the Braceros and ease tensions between the growers and workers.

The California Department of Public Health recommended an immediate change in food distribution to laborers. No deaths were officially reported but Miguel never saw his paisano again and the Asian workers never returned.

In the days that followed, announcements in the papers urged the community to volunteer. The mass food poisoning had depleted the harvest crews. There was no time to lose. The plums were ripening fast and would spoil. The growers had been counting on the Mexicans to rescue the crops, but many of the workers were still recovering. Townspeople turned out to run the dehydrators and drying yards to produce prunes out of the fruit.

Captain Herbert assigned Miguel to the plum fields. Layers of scattered fruit and branches covered the fields. Strong winds had blown much of the fruit to the ground.

Still weak from the food poisoning, Miguel knelt slowly and began picking up each piece of fallen fruit and placing it gently in the bin. Into the night, he and the other able-bodied Mexicans harvested the fruit.

And so, with their work, as they’d promised, the Braceros saved the crops in Colusa.

December 2, 2014