East Los Angeles

Community History

We are currently reviewing the content on this page for accuracy.

Generally encompassing the land east of the Los Angeles River, “East Los Angeles” is a populous area which for many years has been anchored by communities such as Boyle Heights and Lincoln Heights. Home to the Gabrielino Indians for more than two thousand years, the area fell into the hands of the Spanish in the late eighteenth century, with Mexican and American ranchers taking control of the land for much of the nineteenth century. Farmers eventually used portions to grow vegetables and fruit and raise dairy cattle, but agriculture took up only temporary residence, ultimately pushed aside as urban society rapidly expanded.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, East Los Angeles became a popular immigrant destination. In the early 1900s, Russians, Jews, Japanese, and Mexicans all had a significant presence in the area. Living east of the river and working in nearby factories, or traveling by electric rail into downtown Los Angeles, immigrants and their children helped fuel the prosperity of the growing metropolis. By the onset of World War II, East Los Angeles was a nearly exclusively Latino community, soon reinforced by Mexican workers who arrived to man the machines in the area’s burgeoning war industries. Although the face of the city of Los Angeles and its surrounding communities has changed considerably, East Los Angeles has maintained this basic character throughout the last sixty years. As a result of its history as a long-standing Mexican American community, the area of East Los Angeles continues to be studied and documented by scholars from around the world.

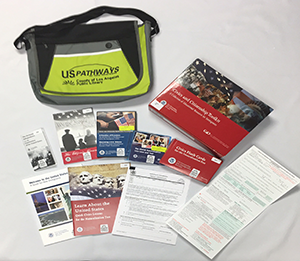

Be sure to check out Foto East LA, a community history project of LA County Library to create an online collection of images depicting the history of one of the nation’s most culturally rich communities. From everyday events to extraordinary moments, we’re gathering historical images taken by locals who have experienced East LA firsthand. We are accepting photos to add to the collection.

Image Gallery

Frequently Asked Questions

Native Americans who lived in the Los Angeles area spoke a language distinct from their neighbors to the North and South of them. They have come to be known as Gabrielino, because many of those who survived European diseases and the disruption of their normal trade patterns and culture went to the Mission San Gabriel in Los Angeles, some voluntarily, others only when confronted by force.

When the Europeans arrived, they discovered many Indian villages between the Pacific Ocean and the San Gabriel mountains. The Gabrielino lived in domed, circular structures with thatched exteriors. Both men and women wore their hair long and used a vegetable charcoal dye and thorns of flint slivers to tattoo their bodies. They required very few clothes, though women usually donned deerskin or bark aprons, and all might wear animal skin capes in cold or wet weather.

Passing through during the mid 1700s as part of Spaniard Gaspar de Portola’s famous expedition from San Diego to Monterey, Padre Juan Crespi observed that the Indians in the area were very friendly. Nevertheless, during the late 1700s and early 1800s, after dominating the Los Angeles area for hundreds of years, those Gabrielino who did not flee were gradually moved to Spanish missions. Many became laborers for local landowners. Most eventually adopted a new, more European lifestyle.

Learn more on the Gabrielino Tongva

For centuries Native Americans made their homes near the Los Angeles River. The late 1700s ushered in Spanish explorers and missionaries whom ranchers and, later, farmers soon replaced. With the blossoming of a local rail system and a maturing economy, tract housing began edging out the farmers early in the twentieth century. In particular, many recent immigrants settled in East Los Angeles. Russians fleeing war and religious persecution joined Japanese, Mexicans, Italians, and Poles in Boyle Heights.

By the mid 1920s, moreover, one third of the 65,000 Jews living in Los Angeles lived in Boyle Heights. Eventually, the European immigrants moved on to suburbs further away. But the Mexican community expanded. In the 1920s, increased immigration spurred by employment opportunities, the encroachment of industry and commerce on downtown Los Angeles neighborhoods inhabited by earlier immigrants, and the accessibility of electrified commuter rail systems to carry workers to their jobs led to a swelling of the Mexican population of East Los Angeles.

By 1930, some 30,000 residents of the community of Belvedere alone were of Mexican descent. Over time, the individual communities on the east side of the river melded into a large Mexican-American community. World War II brought turmoil and tensions with those outside of the community, and in the 1950s and 1960s, massive freeways began to criss-cross the area, bringing with them problems of division and pollution.

Community contours were further changed as neighboring cities, including Monterey Park, Commerce, and Los Angeles, annexed pieces of East Los Angeles. Attempts by residents of East Los Angeles to incorporate as an independent city were unsuccessful. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the uneasy co-habitation of the Latinos of East Los Angeles with their frequently discriminatory neighbors helped ignite the activism of the Chicano movement.

In the 1800s, Mexican and American ranchers used the land for sheep and cattle grazing. As the century progressed, more and more farmers made their homes in the area that would later become East Los Angeles. They planted grains and raised pigs and chickens. Citrus trees, eucalyptus groves, and grape vines, as well as rows and rows of vegetables, sprouted alongside fields of grazing dairy cows. Relatively early in the twentieth century, however, train tracks, paved streets, immigrant dwellings, and factories replaced this bucolic scenery.

Named after Agustin Olvera, Los Angeles County’s first judge and the owner of a home set along the thoroughfare in the 1850s, Olvera Street actually dates back to the late 1700s, when 44 Mexicans settled El Pueblo-present-day Los Angeles. Their community was centered around a plaza, of which Olvera Street was a part. On Easter Sunday 1930, Olvera Street officially opened as a Mexican marketplace, providing Mexican Americans from throughout the greater Los Angeles area with a place to meet, do business, and preserve their heritage. Olvera Street is currently part of the El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historic Monument.

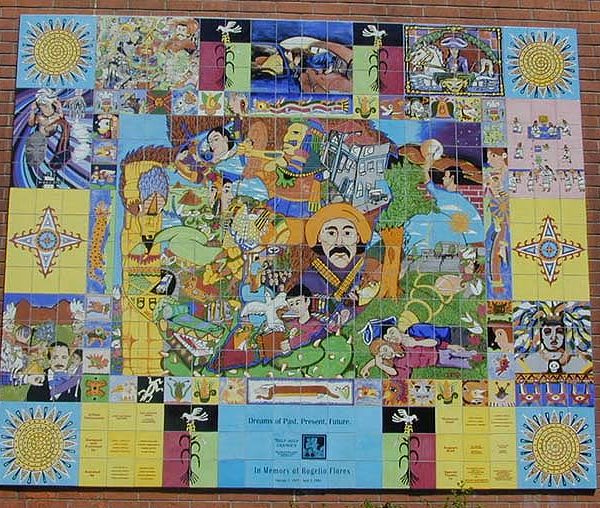

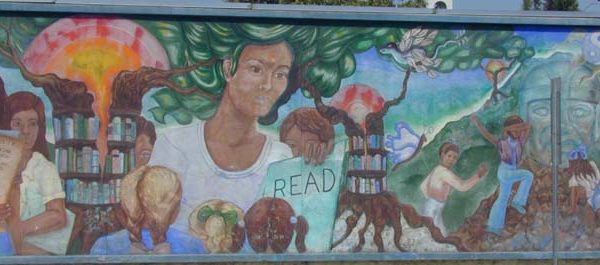

Los Angeles is considered by many to be the “mural capital of the world.” Always a part of Mexican art tradition, murals became a canvas for social and political statements in the hands of a number of Mexican artists in the early twentieth century. Artists in Los Angeles saw similar value in the painting of murals later in the century, revitalizing the art form as a means of expression in the wake of the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

In 1974, arts-activist Judy Baca established a citywide mural program and later helped start the Social and Public Art Resources Center (SPARC). At the end of the 1980s, SPARC introduced “Neighborhood Pride: Great Walls Unlimited,” a program through which SPARC raised funds and commissioned talented artists to paint murals throughout the Los Angeles area.

“Tropical America,” the mural Mexican artist David Siqueiros painted in 1932, depicted an Indian splayed on a double cross with what the artist referred to as “an American imperialist eagle” above his head. Behind the cross were Aztec symbols and a Mayan temple. While some appreciated the mural as art, others thought it was anti-American. Within months, a portion of the mural had been whitewashed, a fate that befell the entire mural within a few years. At present, the mural is covered in preparation for restoration by the Getty Museum.

The Zoot Suit Riots erupted in Los Angeles during June 1943. “Zoot Suits” were extra-large suits with long pants and long coats and were very popular with many young men, including musicians. The press fueled the sentiment against the zoot suits and those who wore them by claiming that these suits used more cloth than was legal under wartime rationing and portraying the wearers of the suits as 4-F’s and gangster types. Public opinion associated the zoot suits with Mexican-American gangs.

The 1942-1944 Sleepy Lagoon Murder trial resulting from the murder of Jose Diaz in August 1942 and the corrupt trial of seventeen Mexican American defendants that followed, served as a precursor to the Zoot Suit Riots of 1943. Leading up to the riots, soldiers and sailors stationed in the Los Angeles area had repeatedly quarreled with young Mexican Americans. The two sides finally clashed violently on June 3 when a group of sailors assaulted a handful of zoot suiters in Venice. The attacks themselves were a destruction of the zoot suits while they were being worn. The newspapers printed photographs of the bloody, bruised, and often naked victims, while they were being arrested.

Word got out that gang members had done the attacking and the following night saw several hundred soldiers and sailors making their way through the streets of East Los Angeles and Los Angeles. In the days that followed, military men and ordinary citizens, with more encouragement than intervention from local police, roamed the streets randomly attacking zoot-suited Mexican Americans, occasionally taking on blacks and Filipinos as well.

The military commanders were slow to take action, in addition, many cab drivers supported this strike against “unAmericanism” by providing cab rides to soldiers and sailors into the city, especially on one particular night, known as the Taxicab Brigade. Only after military commanders barred their charges from East Los Angeles and downtown on June 7-at the urging of Washington officials feeling the pressure of the Mexican government and international public opinion – was the rioting finally halted.

The “Battle of Chavez Ravine” refers to a ten-year dispute over what to do with a certain area of Los Angeles. In the 1940s, Chavez Ravine was a poor, though cohesive, Mexican-American community. Many families lived there because of housing discrimination in other parts of Los Angeles. With the population of Los Angeles expanding and Chavez Ravine viewed as a prime, underutilized location, the city voted to use federal funds to erect an apartment complex to address the severe post-World War II housing shortage. Prominent architects Richard J. Neutra and Robert Alexander developed a plan for “Elysian Park Heights.”

The city had already relocated many of the residents of Chavez Ravine when the entire project came to a halt. Fear of communism was sweeping the United States and loud voices in Los Angeles cried that the housing project smacked of socialism. In the end, the project died. During the failed housing project attempt, the city began to label the area as “blighted” and thus viewed Chavez Ravine as ripe for redevelopment. Some years later, the city made the controversial decision to use the land to tempt the Brooklyn Dodgers to move to Los Angeles. With Chavez Ravine slated to become the site of the new Dodger Stadium, the remaining members of the Chavez Ravine community were forced to relocate.

In the mid 1960s, with blacks demanding their rights, the war in Vietnam heating up, and President Lyndon Johnson pressing ahead with his War on Poverty, Mexican Americans in the United States began to think more about their own social, economic, and political oppression. The Chicano movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s stressed the unique identity of Mexican Americans and encouraged cultural self-awareness and expression. Political and social activism to correct injustices and defeat discrimination were a natural outgrowth of that awareness and a major feature of the movement.

Key issues involved inadequate education, police brutality and the high rate of Chicano incarceration, inadequate services, political gerrymandering and lack of political representation, and the high number of Chicanos dying in the war in Vietnam. The Chicano movement took up many of the demands seen in the Black civil rights movement, such as self-determination and ethnic pride. East Los Angeles, because of its ethnic composition, became the center for Chicano art, literature, expression, and intellectual activity.

Born in the mid 1960s, the Brown Berets started as a group of young Mexican Americans, both men and women, determined to nurture leaders within their own community to facilitate social change and fight injustice. In the face of police harassment, they established an organization called “Young Chicanos for Community Action”-later the “Brown Berets,” after the article of clothing they adopted as a symbol of unity. The Brown Berets became leaders in the Chicano movement, mobilizing their neighbors for protest and action in the late 1960s and early 1970s. They supported the “Chicano blowouts” of 1968, were involved in forming the Chicano Moratorium Committee, and in 1972 occupied Catalina Island for a time in hopes of increasing awareness of the plight of Chicanos. Within the last fifteen years, the Brown Berets, now broken into two factions, have again become active in the Latino community.

In the late 1960s, as was happening with teens across the country, Mexican American teens were breaking out of accepted roles and trying to take charge of their education and futures. Many took on the label of “Chicano” or “Chicana” in spite of the fears and concerns of parents and other adults that they were being too radical or even communist.

Over the course of several months, students at Lincoln High School became politicized and increasingly aware of the inadequacies in educational funding, programs, Chicano and Mexican culture in the curriculum, and of Chicanos on the faculties of the East Los Angeles high schools. They began organizing themselves and educating their peers in the surrounding schools. Feeling the Board of Education was not listening, these students organized a walkout or “blowout” that gained momentum. One day in early March 1968, hundreds of East Los Angeles high school students walked out of their classes.

Over the course of the next several days, hundreds more students from fifteen different schools followed suit. Eventually, police arrested thirteen people on conspiracy charges – though nothing ever came of these. At the heart of the student protests were concerns and frustrations regarding educational conditions in public schools attended almost exclusively by Chicanos where drop-out rates were astronomical and graduates who went on to college were rare.

The students resented the poor physical condition of their schools and the fact that most of their teachers pushed students towards shop courses rather than towards college. They wanted bilingual education, more Chicano teachers and administrators, and courses relevant to their Mexican heritage, not to mention improved cafeteria food. In the end, city education officials did little to meet the student demands, and some twenty years later those who participated, while showing evidence that the demonstrations had significantly impacted their own lives, were still lamenting the problems plaguing the schools of East Los Angeles.

The Chicano Moratorium Committee was a group organized in the late 1960s primarily to protest the war in Vietnam and the disproportionately large numbers of Chicanos being drafted and dying overseas. Chicanos’ poor schooling, poverty, and lack of power, activists noted, made them less likely to resist the draft and more likely to join the military.

The Chicano Moratorium sponsored several large demonstrations in late 1969 and the early 1970s. Though intended to be peaceful protests, one rally in East Los Angeles on August 29, 1970, degenerated into a riot as police clashed with some 20,000 demonstrators. The community history holds that the trouble began during an after-march rally as protesters and families were in Laguna Park (now Salazar Park) watching the concert and speakers. The Los Angeles Sheriff Department called for the crowds to disperse and began advancing with tear gas. The crowd had only one exit available to them and could not exit fast enough and so began resisting.

The chaos extended into the surrounding neighborhood where looting took place. In the end, three people–including Ruben Salazar–were killed, 61 were injured, and more than $1 million worth of property in the vicinity was either stolen or damaged. The anniversaries of this date are often commemorated with marches and rallies throughout the same neighborhood. The National Chicano Moratorium Committee still exists and remains focused on fighting for better education, improved health care, and other rights for Latinos.

Ruben Salazar was the news director of Spanish-language television station KMEX, a former journalist for the Los Angeles Times, and a man committed to educating the Chicano community and empowering its members. His columns served to spark discussion on issues of race, identity, and generational conflict within and outside the Mexican American community. While at first he saw himself as a Mexican American, his most famous column was “Who Is A Chicano? And What Is It the Chicano Wants?” Although Salazar’s life story is yet to be published, his columns are compiled in the book Border Correspondent: Selected Writings, 1955-1970.

Salazar was killed during the August 29, 1970, demonstration, when a tear gas projectile fired by a sheriff’s deputy hit him in the head as he sat inside Whittier Boulevard’s Silver Dollar tavern. Cries of murder and political assassination led to an investigation. Community interest was strong and the inquest into his death was televised locally. But a flawed and biased inquest resulted in no criminal prosecutions, inflaming further the suspicion, anger, and frustration of the citizens of East Los Angeles.

Juana Beatriz Gutierrez and several of her friends founded the group in 1986 to prevent the state of California from building a prison in their neighborhood. Distributing information and holding candlelight vigils each week, they also lobbied in Sacramento. Their actions earned considerable press coverage and, in 1992 the state decided not to build the prison. This success, plus the fact that they were also instrumental in combating an incinerator project, has brought them attention by students of environmental racism and community activism. Now an institution, “Mothers of East Los Angeles” has been involved in conservation programs, health educational campaigns, and raising money for college scholarships for local students.

After Mexico earned its independence from Spain early in the nineteenth century, England, Spain, and France loaned the new country funds to help it survive. While England and Spain eventually decided not to demand repayment, France attempted to conquer Mexico. On May 5, 1862, the Mexican army defeated the French at Puebla, demonstrating Mexico’s commitment to maintaining its identity and freedom and its willingness to fight in defense of those principles. In the United States the Battle of Puebla came to be known as Cinco de Mayo.

While Cinco de Mayo celebrates the Mexican victory against the French at the Battle of Puebla, dies y seis de septiembre celebrates Mexican independence on September 16, 1810. Many people confuse the two. People of Mexican heritage throughout the United States, as well as in Mexico, celebrate Cinco de Mayo with dancing, parades, fireworks, and music to commemorate this event and the spirit it symbolized.

The Los Angeles Public Library’s photo collection has many old photographs of the East Los Angeles area. The Japanese American Museum also has a project on Boyle Heights that has a collection of historic photographs of the community.