Made in the U.S.A.

During the summer of 1997, Timothy McVeigh was tried on television for killing people in Oklahoma. The English stood along the streets outside Westminster Abbey to bid farewell to Princess Diana. And in Los Angeles, our closest thing to Sears – the Woolworth’s on Broadway and 8th — closed its doors after years of declining business.

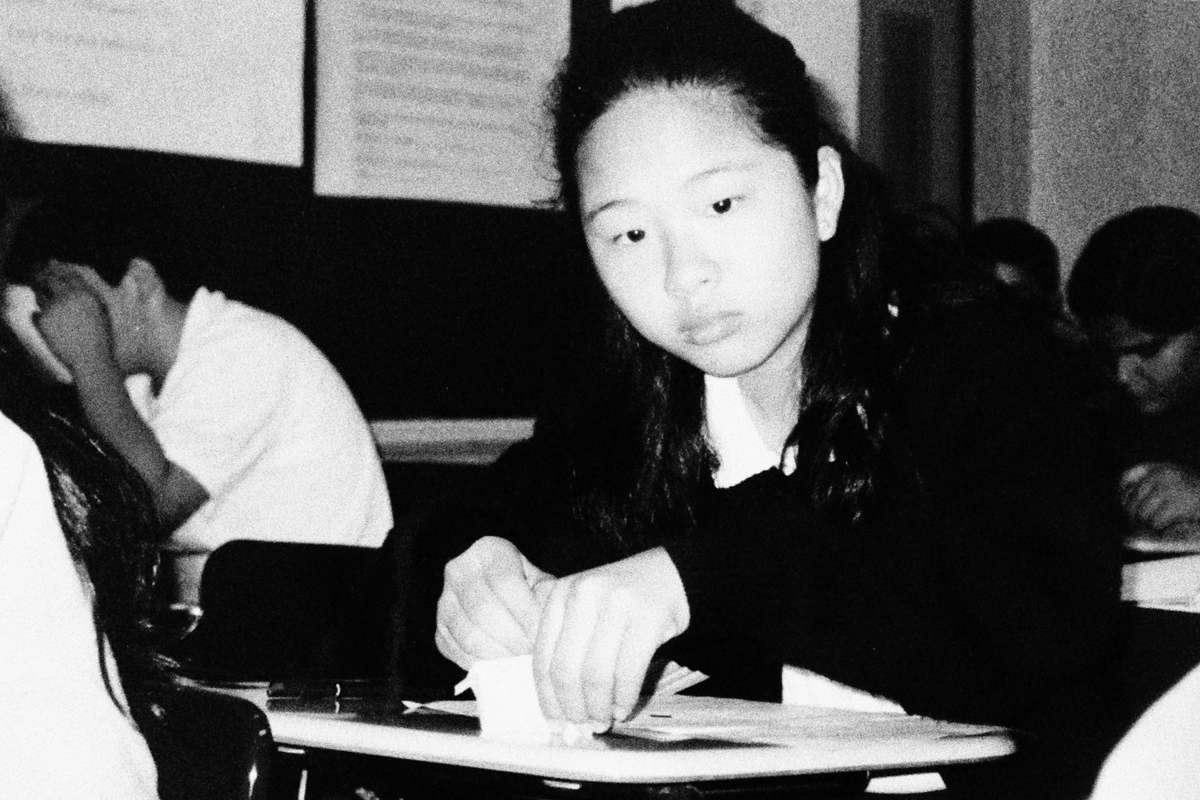

But I knew only a little of that in my small corner of the world on 23rd and Los Angeles streets. I was consumed with having to enroll in summer school and retake sixth grade Algebra.

I told Mr. Alexanian, my Algebra teacher at John Adams Middle School, that I was gravely concerned about having to walk home at 2 pm each day. That was before the B and C tracks kids got out of class, which meant my chances of getting bullied by the other summer school A track girls leaving with me increased. This also meant nobody would be able to call the cops should I get hurt. I would be left bleeding in an alley somewhere and Mom and Dad won’t know how to call the authorities because they don’t speak any English and no one would translate the letters they get at home and ultimately both would get deported back to China. Didn’t he know the consequences of enrollment?

Mr. Alexanian enrolled me anyway.

That summer I got lots of exercise darting out of the school gate at exactly 2 pm and running home. I figured that strategically, I had to vamoose before the other A track girls, and Frances and Susana in particular, got out of class. They would pick on me about the holes in my school uniform and the Payless tennis shoes I wore with the loose flapping soles.

John Adams was one of those schools that consistently scored between a 2 and a 3 out of 10 from GreatSchools.com. Ninety-eight percent of the student population is Hispanic/Latino, two percent African American, and an unlisted contingency of Others, which in 1997, included me and another Chinese kid named Kenny Lu. Typically when other kids met me the second or third question they ask would be, “Is Kenny your brother?” Followed by, “How do you see like that?” Fifty-eight percent of the student body was English proficient, one-hundred percent qualified for free meals, which they endearingly coined “county food,” and two percent of the parents reported to have gone to “some” college. To make us feel better however, our school administrator, Mr. Cortinez, would often say, “Well, at least you’re not at Carver Middle School.”

I thought maybe curling my straight black hair would help me fit in better with the Latina girls, so I begged my mom for a perm. She took me to her hair lady in Chinatown, who gave me the same haircut she gave to everyone else: The Chinese Mom Pouf.

“It’s not ugly,” my mom said, “just look at my hair!”

I envied Kenny because he had friends. His family owned a fast food restaurant and he played basketball. I however had lingering asthma, a hernia, and arthritis in my knees that required me to wear stockings during PE – stockings that we got at Thrifty’s and were either too light or too dark but, either way, never quite matched my skin color. Some days Francis and Susana would throw spitballs at me, and other days it would be gum. Even the one albino kid named Rodolfo had more friends than I.

My dad’s family once owned a business in China, but that was long before I was born. My dad would often recall stories about his father’s humble beginnings and his own childhood growing up in the French Concession in Shanghai before the Cultural Revolution. He told me about his 14 brothers and sisters, about his English-educated mom, about reading western literature, and about his record collection of American swing standards.

My mom on the other hand was the oldest of five kids and they lived in a mud brick hut that their dad had built a few miles from those glamorous French Quarter homes where my father lived. Her mother had more than once sold her own blood during the 1950s to feed her children. My mom grew up with no electricity, no running water, and no education. Chairman Mao’s sweeping reforms during the 1960s and ‘70s were supposed to bring some much-needed equality, but instead plunged the country into poverty, mass starvation, and civil unrest. So when China opened its doors to the world in the late 1980s, we left.

Why me, I often asked my dad. Why do I get picked on so much? Why do I have to be so Chinese-looking? Why wasn’t I born with a last name like Perez or Rodriguez? Why didn’t they give me a sibling to talk to about this kind of stuff? If I had to look so different, why weren’t we at least rich?

My dad admired the US from afar: It was a beacon of democracy and equality. In Chinese, “America” even translated to “country of beauty.” It was the wild west of rugged freedom and infinite possibilities. But in the US, we were back to zero. Without language proficiency, my dad’s degree in engineering meant nothing. My mom was worse off with no formal education beyond the seventh grade. They did what they could in order to eat and as far as rents went, South L.A. was the best we could do.

I rarely got any glimpse of what my parents saw as the promise of the west. The glamour I saw was only on television from those same black and white films my dad watched as a kid. The real world outside of our pink-clapboarded house at 23rd and Los Angeles streets was bleak and unkind. We had warehouses in the neighborhood with gang tags. There was the automotive repair shop across the street, the foul smelling carniceria around the corner that sold expired milk, and prison bars on every window and door on our block. Was this the freedom my dad wanted?

One day after school, with no notice, a carnival came to town. The city made efforts like this in the `90s in hopes they would help revitalize abandoned or underdeveloped areas. It was also a strategy to replace the drive-by shootings and illegal street racings that occurred on Los Angeles Street with safe and family-oriented activities.

So that day there arrived big purple trucks and big green trucks with signs on its sides that read, “Baque Bros Classic Rides & Amusement, Chino, CA.” Piles of thick metal beams and colorful plastic pods were driven in on the backs of long flatbeds. Rides were erected within hours at the foreclosed Knudsen’s milk processing plant across the street from my house. On my way home from school, I saw leathery-faced white men with baseball caps at the lot hammering things.

By nightfall, the Knudsen’s lot, which the day before had only weeds sprouting through its cracks, was transformed into what I imagined Disneyland to be: glowing, glimmering, and vivid. An All-American spectacle of freedom was across the street. Of the rides there, I could see an electric yellow Fun Slide, a big dangling Sea Dragon, and the dazzling Sizzler. There was a Ferris Wheel next to hot pink canopies with propped up bright signs that read “Popcorn” and “Play,” and people lined up around the chain-linked fence waiting for it to open.

My dad was working another of his 24-hour shifts at the motel that day so I had to wait till my mom got home from her sewing factory job. My dad used to scare me and say that I wasn’t allowed to leave the house or answer the phones because the police would come take me away if they found out I was by myself.

At 7:30 pm my mom came home. She put a few dollars in her pocket and walked with me across the street. I had never seen such an arrangement of flashing lights and neon signs. We walked through the cotton candy stands, buttered corn stands, bacon-wrapped hot dog stands, and water gun games. Each corner of the midway was lit with something: Cheese! Drinks! Ride Coupons! The whole place smelled like warm cake and ringed like the inside of a pinball machine. To save money, however, we skipped the food and went straight to the games. I was intimidated by most of the carnival games, so with the two dollars my mom gave me, I opted to toss quarters on plates. I later found that the prize was also a plate.

For the first time there were white people in this part of the town who weren’t police officers or school administrators. They looked average. They were working class, just like us. I would later come to learn that these people were called “carnies,” but at the time I thought they just looked like the Americans on television. The plate stand lady had on an oversized purple shirt and a fanny pack. With her disheveled hair and round face, she asked me, “What are you?”

“Chinese,” I said. “Where do you come from?”

“Nebraska,” she replied. Then she waved to my mom, who nodded and smiled in response.

By 7:50 pm my adrenaline was running high from winning plates, so I decided to take my positive streak to the rides. My mom gave me a few more dollars and on I went to the only two rides with one-person seats: the Dizzy Dragon and the Flying Bobs. The machines consisted of a series of carts attached to a rotating center axis that spun at Daytona-fast speeds. Or at least that’s what it felt like sitting inside of one. For a moment, I had forgotten all about Frances and Susana. Look who was now the king of this fiberglass dragon’s den!

But like a drug addict, I came down hard after the rides stopped. “What would it be like to have a friend on this ride with me?” I thought. Personal realities are like unwelcomed intruders during times of quiet. If only my mom would buy me two more tickets for another hit.

In school, I learned that the name “Lorena” comes from the word “laurel” which meant victory. The first time I ever saw a “Lorena” outside of school was at this carnival. She was with her mom, her brother and cousin Freddy getting cotton candy and I was holding my mom’s hands after being freshly dizzied from the Flying Bobs. I remembered her from class and I remembered she wasn’t mean, so I awkwardly waved to her as we walked past. She waved back, which was expected. What I didn’t expect, however, was when she came up to me and talked. I thought everyone from school would assume I’m some alien from another planet – a weird-eyed, plump-faced, and horrendously-permed creature they’ve never seen before in this part of South Central, Los Angeles. Is this person talking to me? She’s asking me questions about which rides I’ve been on like I’m a normal human being.

And she kept talking to me.

“Have you been on The Zipper yet?” Lorena said.

“Not yet,” I replied.

“Wanna go?”

Yeah.

The Zipper was the fast ticket to being cool for a 12 year-old. Street cred that I desperately needed was purchasable for three ride coupons. Invented in 1968 by Chance Rides, Inc. of Wichita, Kansas, The Zipper with a capital T reached about 56 feet in the air. A plaque on the ride proudly declared, “Made in the USA.” Its center is a long rotating oval with cables around its edges that pulled about 12 cars all spinning at unpredictable G-forces. According to the DomainofDeath3.com, The Zipper is “the most feared carnival ride in existence” because people die on a regular basis riding this thing. Sometimes a car door would come loose; sometimes the whole car would come loose. The point is: it’s dangerous.

While waiting in line for The Zipper, Lorena told me she lived with her mom, her dad, her brother, and her cousin, Freddy. They drove into the U.S. from Mexico when Lorena was still in her mom’s belly. She attributed the successful crossing to her mom’s fair skin and blue eyes. Their apartment was close to the school. Neither of her parents spoke any English, her brother was in high school but fixed cars sometimes, and Freddy’s parents were no longer around, whatever that meant. Then she told me she wanted to get a Ph.D and work for the coroner.

“Dead bodies!” she enthused.

We talked about our favorite TV shows like I Love Lucy and The Simpsons. We talked about our favorite foods, which included Flaming Hot Cheetos and pizza. She told me she wasn’t good at spelling and I told her I learned from watching closed captioning. Corpses aside, we were actually a lot alike.

And then Lorena and I got inside The Zipper, two to a metal pod. A leathery-faced male carny with a Miller Lite t-shirt closed our cage and thundered, “Good luck.” Surprisingly, it wasn’t as large as I thought it would be. The steel mesh made everything very dark inside and it smelled like sweat and rust. Our pod climbed a little higher every time another pair of people got on. We were quiet as our pod climbed ever so slowly to the top. We saw the lights beneath on Los Angeles Street stretching north to Downtown, to that tall US Bank building in the distance. Nothing blocked our view. The night sky seemed endless.

Suddenly someone bellowed something from below. A loud buzz went off. Engines roared and chains ground. We swung high and around, this way and that. With each rotation of the chains our pod spun 360 degrees. We spun over and over. After a minute, a pause, another buzz, and we went backwards. At first slowly, then very fast. All I heard were screams.

When it finally stopped, our pod was eerily quiet. “Lorena, are you okay?” I said. She muttered something unintelligible. A few seconds later, I smelled it. At first it smelled a lot like cheese, but I didn’t eat pizza at school. Was I really that hungry? Then the cheese smell took on a sour tinge. And then I felt her warm vomit on my right arm and leg.

“I am so sorry,” Lorena said. “I’m so embarrassed.” Followed by some more moaning and grumbling.

“That’s ok, I like cheese,” I joked. She laughed. And I thought, “Yes! Now she’ll have to be my friend.” The Miller Lite t-shirt carny gave us a look of horror when he opened our pod door. We kept our heads down in laughter and ran back to our moms, vomit and all.

That was the summer of 1997, when I made my first friend. Things at school were a little easier after that with Frances and Susana. Lorena would find me every day during lunch and eat with me.

Sometimes after school she would even get her mom to walk with me half way home.

November 7, 2015