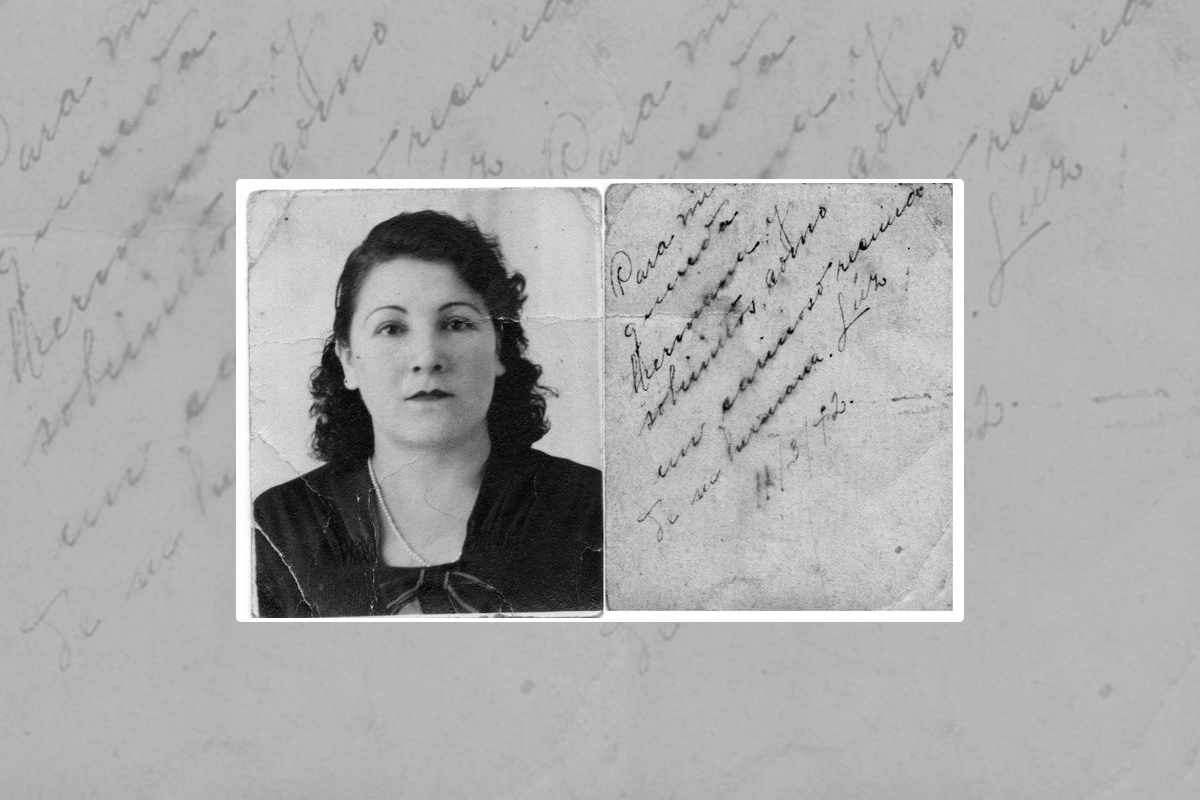

Bringing Luz

In the 1920’s, Luz Solís was living in San Diego with her husband and their two young children.

Luz was raised in Tijuana and had crossed the U.S. – Mexico border daily to attend grade school in San Ysidro.

Her husband, Lupe Tirado, was from Sinaloa; a man with limited education and a strong temperament who worked as a cement finisher. Luz was 16 years old when she married him in Tijuana and, as crossing the border was much easier then, they went to live in San Diego. They lived in a rented modest house downtown on Columbia Street near West Market Street.

She and her sister, Antonia, were born to Ygnacio Solís & María Cañez, a customs agent at the Tijuana checkpoint and his wife. After she married, Luz frequently visited her parents and sister in Tijuana. When her father died, Luz’s mother and sister moved to Santa Paula, California, north of Los Angeles, where relatives lived. Not long after that, Luz’s mother passed away. Antonia remained in Santa Paula under the care of relatives, the Gutiérrez family, until she married. Luz came up often.

One day, Luz returned from a trip to Santa Paula to find her home on Columbia Street empty. Her family had vanished. Her husband was gone. Their children – their son Leocadio and daughter Ascención – were nowhere to be found.

Frantic, Luz went door to door, inquiring with neighbors. She spent days searching. A neighbor informed her that Lupe had fled to his native Mazatlán, Sinaloa. She went there. Back then, it was a trip that took many days. But in Mazatlán she found nothing.

Luz returned to San Diego, destroyed. She continued searching. Yet, unable to afford the rent on her own, she had no other alternative but to find shelter with the Gutiérrez family in Santa Paula. When she gathered enough strength to make it on her own, she moved to Tijuana. For years, she frequently crossed the border into San Diego to search for her children Leocadio and Ascención without success.

By 1930, Luz was living in Tijuana, and remarried to Carlos Savín, a commercial fisherman who followed the fishing routes along Baja California. They divided their time between homes in La Paz and Tijuana, depending on the fishing season. Often, over the years, they crossed into San Diego to visit Luz’s family. When they did, Luz always returned to the house on Columbia Street where she last held her children.

In time, neighbors moved away and the neighborhood was one she no longer recognized. She carried her children’s disappearance like a cross, longing more than anything to find her children. But with every passing year, the longing formed a deep abyss of sorrow.

Luz and Carlos never had children of their own. But the children of Carlos’ brother came to live with them and Luz raised her nieces – Dora and Margarita – and they loved her as their mother.

Every month for as long as she lived, Luz wrote letters to her sister, Antonia, who was by then living in the Mexican state of Zacatecas. In those letters she wrote of the daily events in her life as well as the agony caused by the absence of her children.

In 1986, Luz’s letters became sparse; months went by without any news from her. One day, the letters ceased. Concerned about Luz, Antonia sent a letter to the corner house on Calle Revolución and Sonora, in La Paz, inquiring about her sister. She received no response. Antonia never again heard from her sister.

The memory of Leocadio and Ascención vanished with Luz.

Antonia was my grandmother. I heard the story of my Grand Aunt Luz when I was 9 years old.

It was 1978. I was at my Tía Lupe’s house on Atlas Street in El Sereno, in the living room, cross-sitting on the patterned burgundy carpet. Outside, leaves fell on the low stone wall that surrounded the front porch. Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass played in the background. My mother sat at the dining-room table while Tía Lupe sewed a flowered skirt for me, to be used during Folklorico Dance practice and they laughed as they told what they remembered of the letters their mother, Antonia, received from her sister Luz in Baja California.

Every time a letter arrived, they said, Antonia would sit them around the small coal-burning stove, which simultaneously heated the cast- iron clothes iron and cooked the beans in the earthenware pot as she read the news from the family that lived so far away. Every detail of the letters was animated by Antonia’s tone and pitch, except when the news was sad; then her voice became somber and sometimes she didn’t read aloud what was written.

As the memories of the letters unfolded, the boisterous laughs of my mother and her sister grew quiet and still, Herb Alpert became faint and they told the story of Luz and her children. I never forgot that story.

Years later, when I was in my twenties – seventy years after the disappearance of Leocadio and Ascención – I began to search for them.

My quest began with a leather-bound photo album, carefully arranged throughout the years by my Abuelita Antonia. This collection of photographs captured moments in time described in the letters. Every year, in the winter recess, when I visited my Abuelita in Zacatecas, I immersed myself in the stories the pictures conveyed. I linked the people in the photos to the names and the events in the letters. I connected myself to these memories left behind in the photographs. Two photos were absent from the collection and deserved a place alongside the others.

My father and sister humored my persistence in searching for documents that would serve as clues to the whereabouts of Luz’s missing children. But they could not understand why. My mother, in her heart, longed to locate them but didn’t think the pursuit would be fruitful. My cousins thought I was mad. Let the past be, they would say. Why disturb what was to be? Why does it matter, it happened so long ago? Who is Luz? Let the story that faded into the walls remain there, to protect those who lived and suffered.

I obtained Leocadio and Ascención’s birth certificates registered in San Diego, then, I located a 1920 Census record. It listed a Guadalupe Tirado as a head of household; it listed Lucy as his wife and Oscar as their one year old son. They were renting a house on Market Street in San Diego. However, I was perplexed by the recorded name for their son: Oscar. His age was accurate. Could this be Luz’s family?

I came across several border-crossing records for Luz Solís and Guadalupe Tirado and a U.S. World War I Draft Registration Card for Guadalupe. The border crossing records and the draft registration document identified Luz Solís as Guadalupe Tirado’s wife. I revisited the 1920 Census record to check the address and matched a border crossing recorded about the same year. The Tirado family in the 1920 Census had to be Luz’s family. But was Luz’s son named Leocadio? Was “Oscar” his first name and Leocadio his middle name? I grew more obsessed with the search.

In the 1930 Census, I found a Guadalupe Tirado, who was married to another woman named Felicitas. They lived on 13th Street in San Diego. Their two oldest children were the same age as Leocadio and Ascención would have been, but their names were Eugenio and Maria. In the 1940 Census, Guadalupe and Felicitas Tirado lived on Pickwick Street in San Diego. The two oldest children’s names were now Eugene & Mary.

I searched the name Eugene Tirado on the internet and was linked to the Korean War Casualties website. My heart immediately sank. I clicked on the link. “Eugene L. Tirado, born on 1918, killed in Action 26 Mar 1951, Sergeant First Class, Army” appeared on the computer screen. My eyes focused on his middle initial. This had to be Leocadio.

I sought his military records. The Report of Internment for Eugene L. Tirado identified his birthdate. It matched Leocadio’s: Dec 9, 1918. The typed record also had a bonus; in blue lead, the letters “e” and “o” were added by hand to the “L.” I thought of Luz and my eyes flooded with tears.

Through it all, for 20 years, I kept on, convinced I could find these children. I searched census indexes at the local Family Search Library, requested mail-ordered photocopies of birth records from the San Diego County Registrar and census records from the National Archives, visited the Los Angeles Public Library Genealogy Department, maneuvered through microfiche, microfilm, record books, and scoured the sources of data brought on by the dawning of the internet. It led, in the end, to the realization that one of her children was killed at war years before I was born.

In August 2010, I posted a snippet of Luz’s story on Ancestry.com and I also left a note on a message board of a person who had Eugene Leo Tirado on a family tree. Six months later, I received an email from a woman named Frances.

Frances was 68 and she was the daughter, she said, of Eugene Tirado.

She was living in Connecticut, where she raised her family and had resided for over 20 years. Frances said she was born in San Diego and had grown up there, too, until she left for college. After graduating, she married and cared for her two children. Her former husband’s job promotions moved her family to the East Coast, where she found work as an administrative clerk. Frances also had an interest in family history – particularly the family of her birth mother, who had died when Frances was so young and whom she therefore knew little about. She had been researching and developing her family tree for two years by then.

Frances had never heard of Luz Solis.

Her father Eugene and Aunt Mary had grown up in San Diego, she said. The homes their father rented before he purchased a lot on Pickwick Street were just blocks from the one where they last lived with their mother, Luz.

Eugene married a woman who gave birth to Frances and two siblings. The woman died giving birth to their third child, who also died. Frances was only 11 months old at the time of her mother and sister’s deaths. Eight months after, Eugene enlisted in the army; left his two children in the care of his parents, Lupe and Felicitas.

Felicitas was a gentle, pious soul and loved them as if they were her own. Lupe isolated himself in his room after work to escape the noise the grandchildren would create. In 1946, Eugene re-married in Alabama, where he was stationed, and a son was born the following year. He re-enlisted in the Army in 1950 and was a member of the 187th Airborne Infantry Regimental Combat Team when he was killed in action in Korea.

His sister Mary, meanwhile, married a career Air Force officer. They had two children. Lupe sent Frances to live under Mary’s guardianship about the time Eugene re-enlisted.

Soon Frances and I were e-mailing each other daily. She told me about her father, Eugene; he was the life of every party and always wore a smile. He loved Frances and her brother and was always good to them. We exchanged pictures. Eugene did have a beautiful smile just like my mom and her sisters. Mary was the spitting image of Luz.

Frances scarcely knew her Aunt Mary when she was sent to live with her. Mary doted on her two children, as any mother would, but resented having to look after a third child – a child not her own.

Frances had always been told that Luz, her grandmother, had abandoned the family for another man. Frances was shocked to learn this was not true, and upset that her grandfather had put Luz through such misery. But she said it explained a lot.

Throughout her life, Mary always felt cast aside, abandoned by her mother. Before she married, as the only daughter, Mary was given the charge of her four younger half-brothers along with household chores. Once married, she seldom visited her family, though they lived in the same city.

Mary passed away on January 18, 2010 in Escondido, having lived her entire life twisted by a lie her father told. She and her brother, Eugene, are buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego.

Lupe Tirado was a handsome and responsible man. He worked hard all of his life to provide food and shelter for his family; but he was violent. Everyone feared him. His grandchildren had to be careful not to touch anything when they visited his home. Lupe was short-tempered with his sons if they did not respond to his first call. He was proud of whisking Felicitas away on a horse, in Tijuana, to care for his two little children.

Lupe never mentioned Luz’s name, nor spoke of his past. I suppose we will never know why he abandoned Luz. Years later, Felicitas and Lupe divorced. Lupe married a third woman – a marriage that also ended in divorce.

Frances and I continue to communicate through e-mail, Facebook and an occasional call. She is my mother’s age – now 73; born the same month. My mother and Frances resemble each other at this age: straight, short dark hair with whisks of grey and smiles that light up a room.

The day I received the first e-mail from Frances, I phoned my mother. There was a moment of silence on her end.

My mother grew up without any cousins. She only speaks Spanish and Frances speaks English only. Frances’ daughter and I serve as their interpreters while on phone calls and translators of letters. Google Translate has also played a part, though the translations are imprecise and puzzle my mother.

I now have photographs of Leocadio and Ascención.

“Sylvia,” Frances said, “you have come into my life bringing Luz.”

About a month after our first email encounter, I had a dream that Luz was a fairy trapped in a glass jar. She was screaming asking for her release but she was inaudible. Frances and I worked in unison to release her and when we did, she flew away.

January 6, 2016